The (Re)Construction of the “Groupie” in the Late 1960s and Early 1970s

- cat joy

- Jul 31, 2022

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 10, 2022

The progressive/transgressive relationships shared between the ”Girls Together Outrageously” were framed to evidence the arguments put forth in “The Groupies and Other Girls”.[1] Source: Groupies and Other Electric Ladies: The Original 1969 Rolling Stone Photographs via Google Images, Credit: Baron Wolman.

Rolling Stone’s 1969 issue titled “The Groupies and Other Girls” played an unprecedented role in the creation of the “groupie” identity as not only a nationally syndicated publication, but one which positioned itself as an authority on “groupies” – having documented and observed a variety of girls identifying as the term across the nation.[2] Much scholarship on “groupies” has analysed how this issue connected all girls/women that identified as any strand of “groupie” to sexual support by inextricably linking the term “groupie” to transgressive sexuality through a framework of psychoanalytical pathologizing.[3] In this entry on the “groupie’s” transformation covering the early 1970s, I will be dissecting the issue’s focal article, “The Groupies and Other Girls”, through a binding of Coates’ framework that the issue’s perspective was to darkly eroticize/pathologize the “groupie” identity,[4] and Larsen’s, that it intended to malign the gendered identity of “groupie” through a separation of sexual supporters (“groupies”, “starfuckers”) and domestic supporters (“wives”, “muses”).[5]

Pamela Des Barres, who confides in I’m with the Band she believed the “The Groupies and Other Girls” article intended to portray “groupies” impartially, photographed for the Rolling Stone piece.[6] Source: Rolling Stone via Google Images, Credit: Baron Wolman.

The thesis of Hopkins, Burks and Nelson’s, “The Groupies and Other Girls”, I argue is “groupies”, “think of them-selves as unselfish vehicles of love”, but internal counterculture participants and spectators, “those who’ve studied the groupie ethos”, “see them otherwise”.[7] Across their interviews with the Los Angeleno GTOs ("Girls Together Outrageously"), Chicagoan “Plaster Casters” and San Franciscan Trixie Merkin and Anna, as well as anonymous “groupies” from their communities, the reporters investigate the girls/women’s relationship to relationships with musicians and other countercultural members.[8] The methodology of analysis is psychoanalysis and the conclusions drawn are that excessive/transgressive sexuality and femininity are the root of the “groupie” identity (while interviews with and a discussion of male-identifying “groupies” are included, the reporters frame them as intensely disrespected “roadies”, members of a rock group’s team of music production assistants).[9]

Miss Christine and Miss Pamela of the GTOs communicate their great adoration of one another for “The Groupies and Other Girls”.[10] Source: Groupies and Other Electric Ladies: The Original 1969 Rolling Stone Photographs via Amazon, Credit: Baron Wolman.

Quotes and lyrics from musicians sandwich and cut up the girls and women’s testimonies so as to connect the “groupies” feelings of empowerment and connection to the disrespect and mockery their (expressed or framed to be sexual/erotic) support is internally associated with in the perspectives of those who receive it.[11] Moreover, Hopkins, Burks and Nelson consult scholastic sources, predominantly psychologists, to link sexual support to childhood and past traumas, mental illnesses and disorders, drug use and more general countercultural afflictions like alienation, low self-esteem and lack of ambition/direction.[12]

In interviews with “groupies” and musicians alike, one can discern an established binary between exclusively sexual support and artistic/ideological support that is accompanied by sexual support. “Starfuckers” is the term quoted early on as a referent for the former.[13]

A group of Los Angeles’ “baby groupies”. As primarily sexual (and occasionally ideological/artistic) supporters of rock groups, Hopkins, Burks and Nelson position “baby groupies” as “groupie-starfuckers”.[14] Source: Creem via Dazed, Credit: Creem.

Those “groupies” that provide domestic, as in practical, emotional, familial, support, differentiate and are positioned as different than “starfuckers”.[15] “Groupies” that provide extra-sexual, social reproductive support commonly use terms like “muse” and “wife [to-be]” to describe how they identify/visualize their location in the structure of the counterculture.[16]

A rephrasing of Pamela Des Barres’ examination of the “baby groupies”.[17] The division between “groupie-muse/wives” and “groupie-starfuckers” supported and intensified by Hopkins, Burks and Nelson is articulated (by Des Barres, as well as the podcast hosts).[18] Source: Muses on Listen Notes, Credit: Muses.

From Hopkins, Burks and Nelson’s article two “groupie” types emerge, “groupie-starfucker” and “groupie-muse/wife”, with the authors more critically narrativizing the former’s testimony (ex. placing it between pejorative quotes or lyrics, or it following/being followed by critical statements).[19] Throughout the article the term “groupie” is used alone to reference “groupie-starfuckers”, when “groupie-muse/wives” are in most cases documented as not just “groupies” but also “muses”, “wives”, “girlfriends” or a kin term.[20]

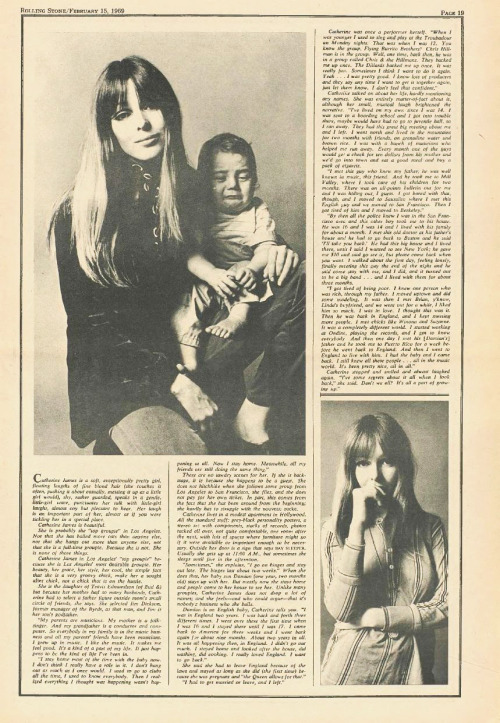

Catherine James with son Damian in Hopkins’ Groupies and Other Girls paperback. James was a muse to and girlfriend of artist Jackson Browne, after acting as a domestic supporter to a number of American and British artists in the 1960s.[21] Source: Rolling Stone via Google Images, Credit: Rolling Stone.

“Groupie” as an identity therefore, as is represented in “The Groupies and Other Girls”, is the same as that of “starfucker”, but not of “muse” or “partner”.

In the early 1970s, impelled by the disconnection between the idea of “groupie-starfucker” as the “groupie” identity that had circulated internal and external the rock counterculture by news and fiction media, and one’s own identity, there was a crisis in the “groupie” discourse and space.[22] Significant self-identified “groupies” of the 1960s severed from the label and criticized girls and women that provided predominantly sexual support to rock groups, among which was the nascent “baby groupie” collective in Los Angeles.[23] The GTOs maintain their identity as offering all forms of support to rock groups in an interview with Hopkins for the Groupies and Other Girls paperback reprint of the Hopkins, Burns and Nelson 1969 Rolling Stone article.[24]

A 1970 radio advertisement for a popular in America British film which reproduces and capitalizes off of the conflation of the “groupie” identity with the “groupie-starfucker” identity.[25] Source: Eagle Films radio press release via YouTube, Credit: Eagle Films.

The attitudes expressed by the GTOs, the ultimate synecdoche of “first generation groupies”, are reflected and fleshed out by the “groupie-muse/wife” collective, based on the historic group itself, the “Band-Aides” in Cameron Crowe’s Almost Famous.[26]

Penny Lane, mirroring Pamela Des Barres and the GTOs distinguishing themselves from the “groupie” label at the turn of the 1970s,[27] distinguishes between “Band-Aides” and “groupies”. Source: Almost Famous via YouTube, Credit: DreamWorks Pictures.

Penny Lane, a filmic representation of Des Barres developed from Crowe’s interviews with her on tour with Led Zeppelin in 1970,[28] differentiates “groupie-starfuckers” and “groupie-muse/wives”: “We are not groupies…Groupies sleep with rockstars ‘cause they want to be near someone famous. We’re here because of the music, we are Band-Aides…We inspire the music”.[29]

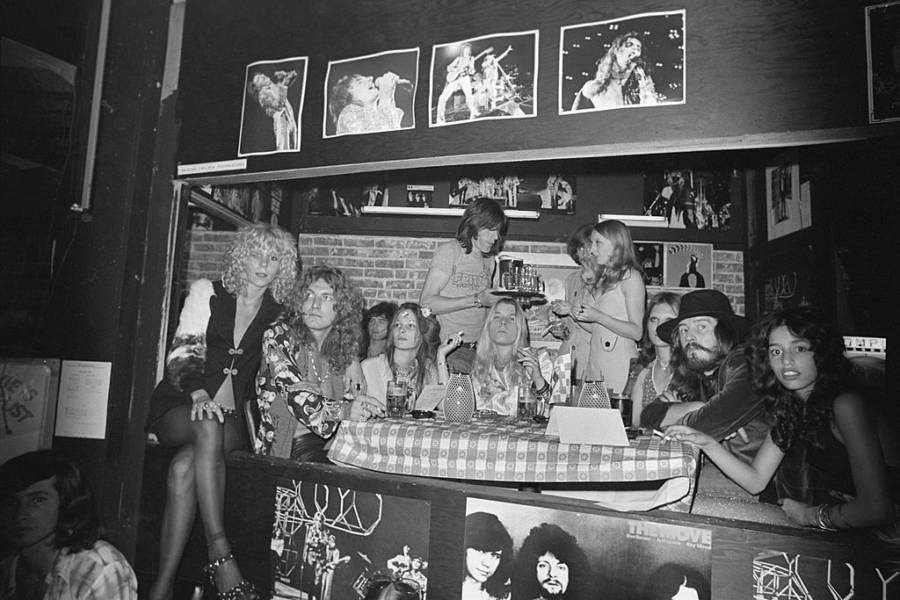

“Baby groupies” in the company of Led Zeppelin. Sapphire, a member of Almost Famous’ representation of the GTOs,[30] criticizes the film’s representation of this second generation of groupies for not being “true” supporters.[31] Source: Getty Images via All that’s Interesting, Credit: Michael Ochs Archive.

Sapphire criticizing the “new girls” who “have no idea what it is to be a fan…to truly love some…piece of music or some band so much that it hurts”.[32] Source: Almost Famous: The Bootleg Cut via YouTube, Credit: DreamWorks Pictures.

The leading agent moving mainstream society to determinately associate the “groupie” term with the “groupie-starfucker” identity in the early 1970s and which encouraged internal countercultural members to evacuate the “groupie” term/identity of any denotation besides “groupie-starfucker” was Grand Funk Railroad’s 1973 “We’re an American Band”.[33] Each stanza of the song’s two verses references girls or women offering or providing the band sexual support, conflating female support of rock groups with sexual support.[34]

In their representations of (“Sweet”) Connie Hamzy and other unnamed female sexual supporters, Grand Funk Railroad widely disseminate the archetype of the “groupie-starfucker”[35]. Source: Grand Funk Railroad Live 1974 via YouTube, Credit: Grand Funk Railroad Archive.

The lyrics’ writer (the band’s drummer Don Brewer), different from the tradition of 1970s rock groups creating music about their female supporters that would develop in the wake of “We’re an American Band”,[36] does not narrativize the girls/women’s sexual support as pitiful, embarrassing or shameful.[37] Counter-hegemonically the “groupie-starfucker” is celebrated, as sexual support was in the mid-to-late 1960s rock counterculture. However, unlike female sexual support in the earlier period – which predominantly accompanied artistic/ideological and/or domestic support [38]– in this context, it is positioned as a commodity girls and women trade for intimacy with and proximity to the band (“Now these fine ladies, they had a plan; They was out to meet the boys in the band; They said, ‘Come on dudes, let's get it on’”).[39]

A newspaper interview with “Sweet Connie” (Hamzy) that testifies to her characterization as “groupie-starfucker” in Grand Funk Railroad’s We’re an American Band.[40] Source: Arkansas Democrat-Gazette via Google Images, Credit: Connie Hamzy.

The centrality of “groupie-starfucker” culture to the American rock counterculture in the early 1970s was clearly communicated by “We’re an American Band”, (re)informing mainstream society what female support of rock groups looked like, and the profound success of a rock group confessing the “private” debauched episodes internal the rock counterculture in song galvanized many other intercontinental rock groups to recreate and reconstruct the practice.[41]

Endnotes

1. Jerry Hopkins, John Burks, and Paul Nelson, “The Groupies and Other Girls,” Rolling Stone, February 15, 1969, https://www.rollingstone.com/feature/groupies-gtos-miss-mercy-plaster-caster-75990/.

2. Norma Coates, “From the Vaults: Teenyboppers, Groupies, and Other Grotesques: Girls and Women and Rock Culture in the 1960s and early 1970s,” Journal of Popular Music Studies 31, no. 3 (2019): 43, https://doi.org/10.1525/jpms.2019.313005.

3. Gretchen Larsen, “‘It’s a man’s man’s man’s world’: Music groupies and the othering of women in the world of rock,” Organization 24, no. 3 (2017): 406, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1350508416689095.

4. Coates, “Teenyboppers, Groupies, Other Grotesques,” 43-46.

5. Larsen, “It’s a man’s world,” 406-409.

6. Pamela Des Barres, I’m With the Band, read by the author (Newark: Audible Studios, 2011), Audible audio ed., 11 hr., 9 min.

7. Hopkins, Burks, and Nelson, “Groupies and Other Girls.”

8. Hopkins, Burks, and Nelson, “Groupies and Other Girls.”

9. Hopkins, Burks, and Nelson, “Groupies and Other Girls.”

10. Des Barres, I’m With the Band.

11. Coates, “Teenyboppers, Groupies, Other Grotesques,” 45.

12. Hopkins, Burks, and Nelson, “Groupies and Other Girls.”

13. Hopkins, Burks, and Nelson, “Groupies and Other Girls.”

14. Hopkins, Burks, and Nelson, “Groupies and Other Girls.”

15. Hopkins, Burks, and Nelson, “Groupies and Other Girls.”

16. Hopkins, Burks, and Nelson, “Groupies and Other Girls.”

17. Des Barres, I’m With the Band.

18. Hopkins, Burks, and Nelson, “Groupies and Other Girls.”

19. Hopkins, Burks, and Nelson, “Groupies and Other Girls.”

20. Hopkins, Burks, and Nelson, “Groupies and Other Girls.”

21. Lisa L. Rhodes, Electric Ladyland: Women and Rock Culture (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), 164-166.

22. Hopkins, Burks, and Nelson, “Groupies and Other Girls.”

23. Karolina Karbownik, “Speculation Over the Love for Rock Music: Media Constructions of Groupies Between the 1960s and 1970s,” Studia de Cultura 13, no. 2 (2017): 50, https://studiadecultura.up.krakow.pl/article/view/8875/8143.

24. Larsen, “It’s a man’s world,” 413.

25. Karbownik, “Media Constructions of Groupies,” 49-50.

26. Des Barres, I’m With the Band.

27. Karbownik, “Media Constructions of Groupies,” 51.

28. Karbownik, “Media Constructions of Groupies,” 51.

29. Almost Famous: The Bootleg Cut, directed by Cameron Crowe (2000; Universal City, CA: DreamWorks Pictures, 2002), DVD.

30. Karbownik, “Media Constructions of Groupies,” 51.

31. Almost Famous: The Bootleg Cut, dir. Crowe.

32. Almost Famous: The Bootleg Cut, dir. Crowe.

33. McKenzie K. Hartmann, “Did I Want to Be with the Band? A Study of Feminism and Consent in the Time of Sex, Drugs and Rock n’ Roll,” (BA thes., The University of Texas at Austin, 2019), 61.

34. Grand Funk Railroad, We're an American Band, Apple Music track, on Greatest Hits, 2006, streaming audio, 3:27, https://music.apple.com/ca/album/greatest-hits/715534629.

35. Hartmann, “Consent in Rock,” 49.

36. Karbownik, “Media Constructions of Groupies,” 51.

37. Grand Funk Railroad, We're an American Band.

38. Des Barres, I’m With the Band.

39. Grand Funk Railroad, We're an American Band.

40. Grand Funk Railroad, We're an American Band.

41. Hartmann, “Consent in Rock,” 49.

Comments